So beautiful and so lost: “Va Pensiero”

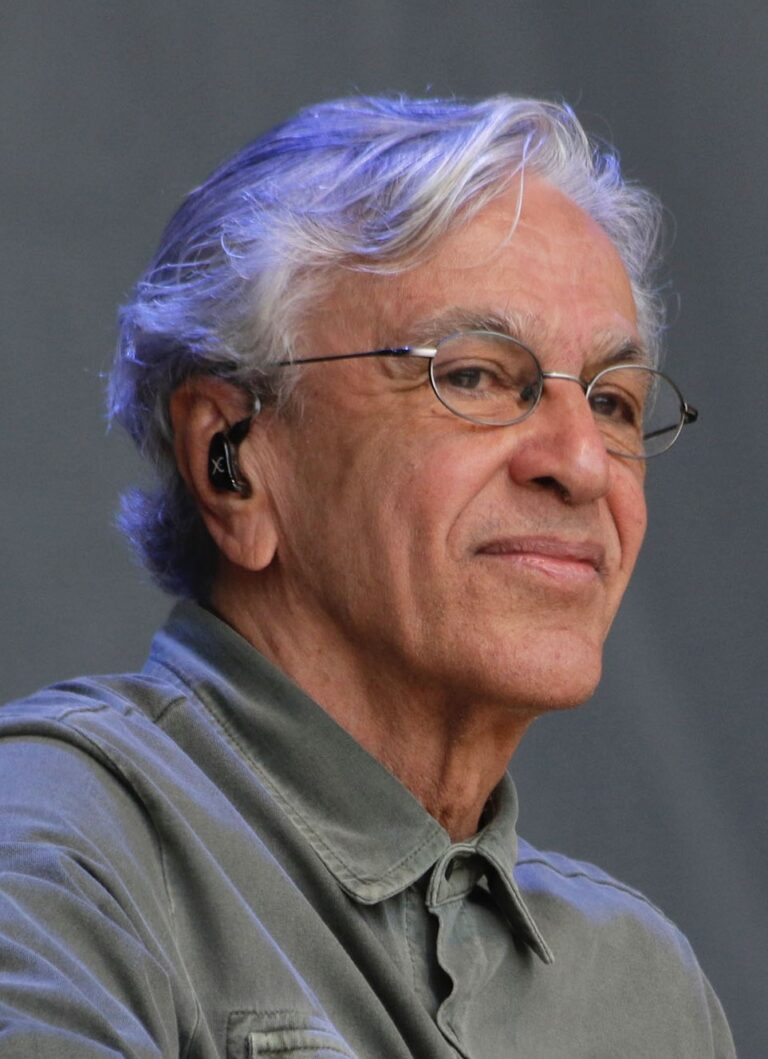

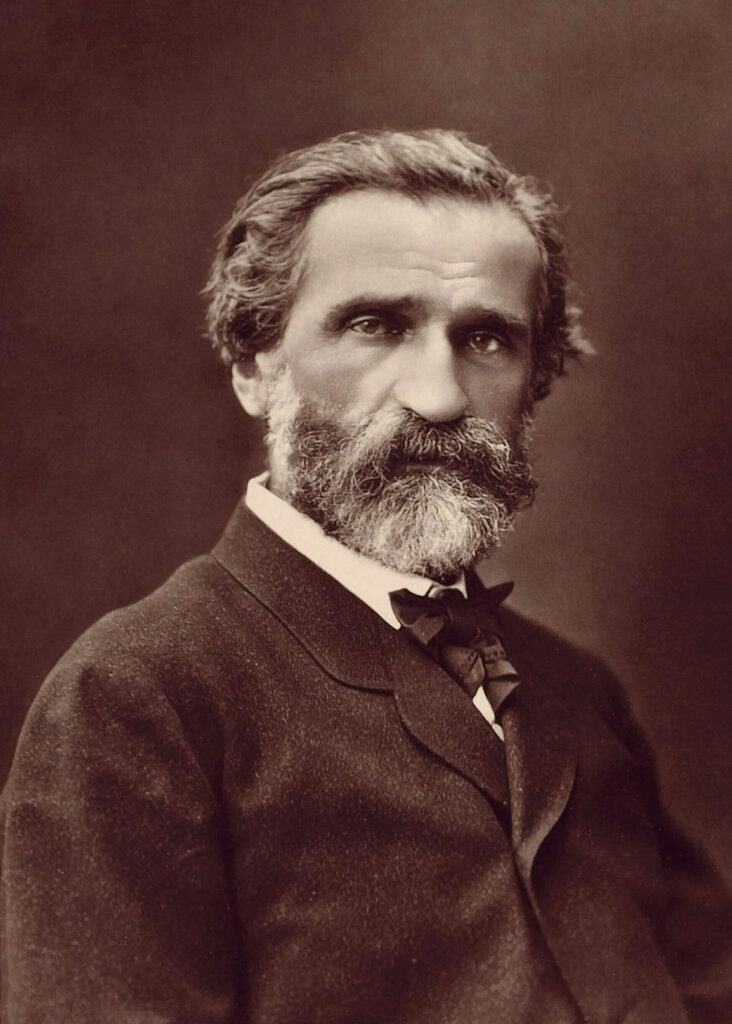

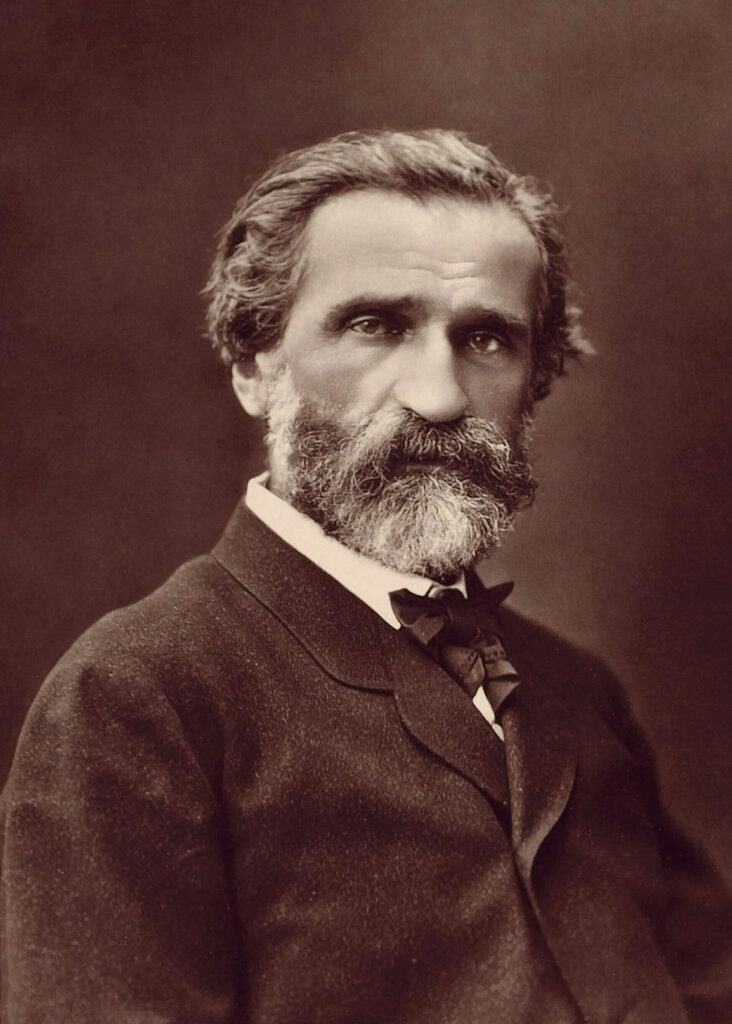

As Verdi lay down the quill with which he had just penned the famous notes to “Va Pensiero,” he could hardly imagine the song would still resonate with his nation over a hundred years later. He was still in Milan at the time, still at the first stages of his budding career, still many years and kilometres away from the success he later enjoyed in his countryside villa in Parma. In fact, his wife and infant children had just died from an outbreak of tuberculosis that had grasped the sickly city of Milan. He was facing financial hardship, as he had since his meagre childhood. His career was at stake, with several early flops not boding well for his future prospects. The glum fog of the north did little to lift his soul, which was used to being sun-kissed in the Emilia Romagna region. And yet, in the face of such misery, he found the inspiration for beauty. That is the power of art.

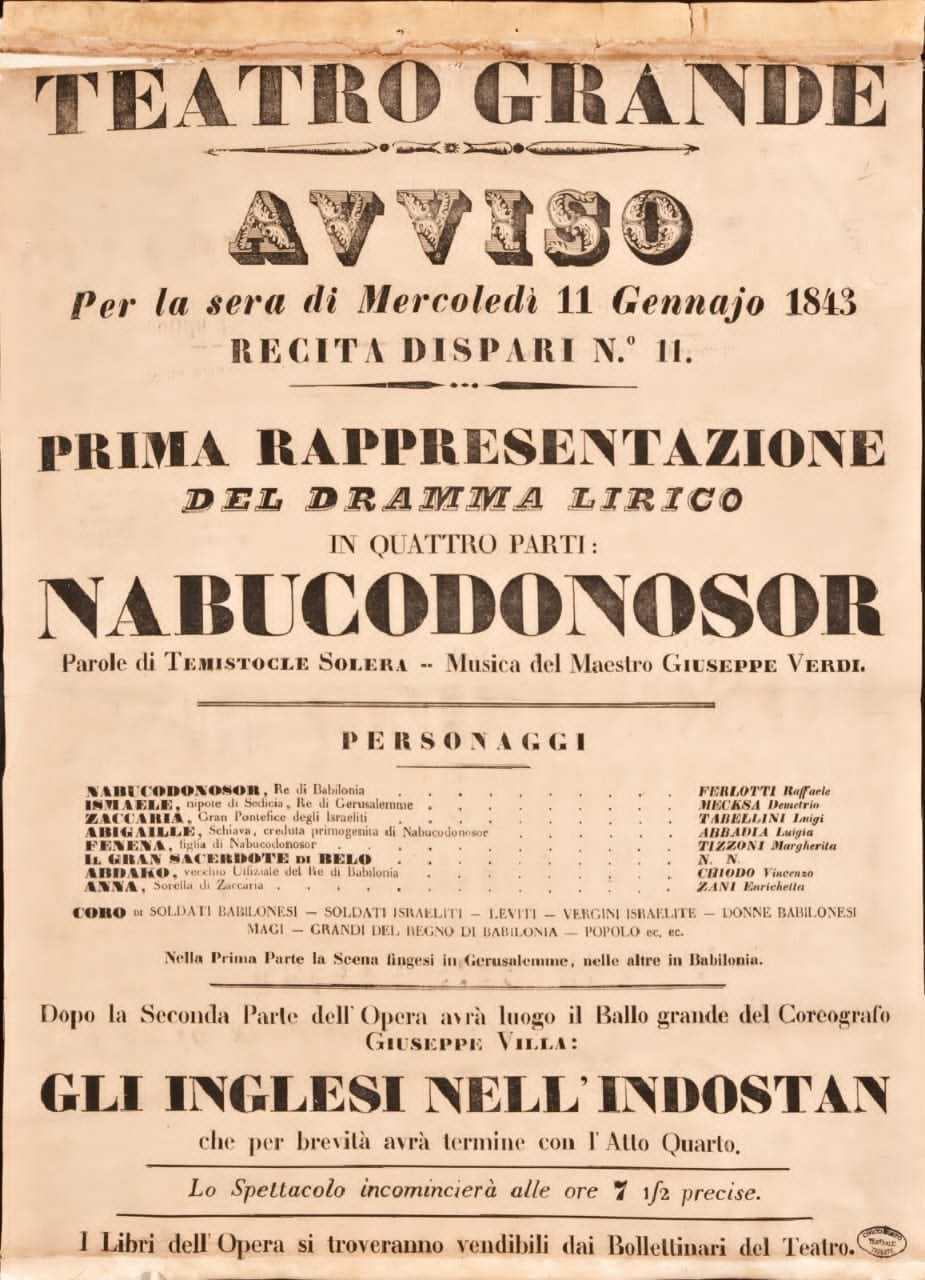

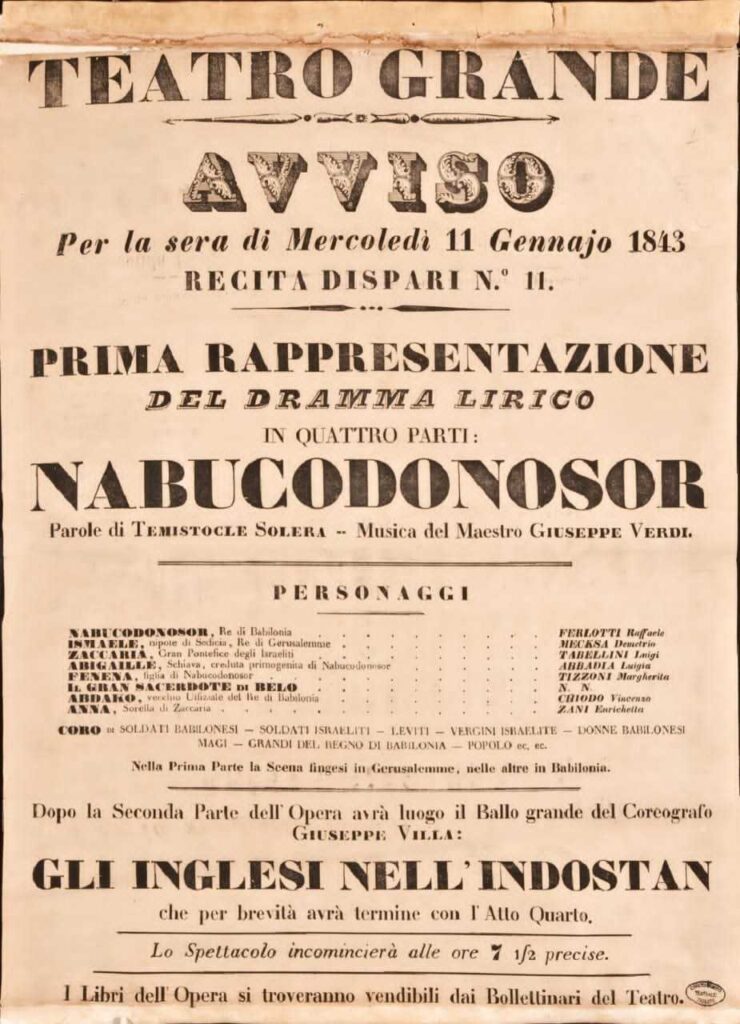

The coro, the chorus, was to serve as the Act III opening to the opera Nabucco, a biblical story of mythic magnitude. Colossal scales are the essence of opera, and this narrative abounded in them. The protagonist, the Babylonian king Nabucco, attacks, conquers and exiles Jews from their homeland, while a political romance spins its threads in the background. Intrigues, death sentences, illegitimate births and love triangles swirl up, appropriately, into a Babylonian tower, only to be torn down to destruction. And the music comes nothing short of this story: sumptuous and awe-inspiring, it puts into musical notes the colossi of ancient powers and cultures.

As Verdi lay down the quill with which he had just penned the famous notes to “Va Pensiero,” he could hardly imagine the song would still resonate with his nation over a hundred years later. He was still in Milan at the time, still at the first stages of his budding career, still many years and kilometres away from the success he later enjoyed in his countryside villa in Parma. In fact, his wife and infant children had just died from an outbreak of tuberculosis that had grasped the sickly city of Milan. He was facing financial hardship, as he had since his meagre childhood. His career was at stake, with several early flops not boding well for his future prospects. The glum fog of the north did little to lift his soul, which was used to being sun-kissed in the Emilia Romagna region. And yet, in the face of such misery, he found the inspiration for beauty. That is the power of art.

The coro, the chorus, was to serve as the Act III opening to the opera Nabucco, a biblical story of mythic magnitude. Colossal scales are the essence of opera, and this narrative abounded in them. The protagonist, the Babylonian king Nabucco, attacks, conquers and exiles Jews from their homeland, while a political romance spins its threads in the background. Intrigues, death sentences, illegitimate births and love triangles swirl up, appropriately, into a Babylonian tower, only to be torn down to destruction. And the music comes nothing short of this story: sumptuous and awe-inspiring, it puts into musical notes the colossi of ancient powers and cultures.

“Va Pensiero” is sung by the Israelites once they have been cast away from their homeland, gently longing to return. As in a dream, sombre woodwinds play the first chords, like the light breathing of calm sleep. A moment of intense violin stirring is dissipated by a harp, as though emerging out of the haze of sleep and finding the clarity of inspiration. When the chorus opens their mouth, it is in an ethereal sotto voce, sustained like a lullaby.

The libretto, by Temistocle Solera, recounts the glories of the Israeli homeland: its slopes and hills imbued with the fragrancies of the natal country; the temples and towers, toppled in their tarnished splendour; the harps of the prophets of old. It is at once both a hymn to the glory of their nation, while also being a singularly visceral appeal to the senses, with smells and sounds reverberating in Israelite hearts. Above all, it is the power of these memories that so vigorously propels this painful longing, inducing to an overpowering sense of loss at the glory gone by.

“Va Pensiero” is sung by the Israelites once they have been cast away from their homeland, gently longing to return. As in a dream, sombre woodwinds play the first chords, like the light breathing of calm sleep. A moment of intense violin stirring is dissipated by a harp, as though emerging out of the haze of sleep and finding the clarity of inspiration. When the chorus opens their mouth, it is in an ethereal sotto voce, sustained like a lullaby.

The libretto, by Temistocle Solera, recounts the glories of the Israeli homeland: its slopes and hills imbued with the fragrancies of the natal country; the temples and towers, toppled in their tarnished splendour; the harps of the prophets of old. It is at once both a hymn to the glory of their nation, while also being a singularly visceral appeal to the senses, with smells and sounds reverberating in Israelite hearts. Above all, it is the power of these memories that so vigorously propels this painful longing, inducing to an overpowering sense of loss at the glory gone by.

As the coro reaches its apogee, they appeal for the strength to bear their suffering in virtue. This is perhaps what gives “Va Pensiero” its struggente, poignant power: the resolve to rise above the greatest of hardships, in the face of utter loss, for the sake of one’s faith. It is something that goes beyond mere national identity or patriotism, or even national loyalty, but a belief that even in the worse of times, righteousness will prevail. It is, in fact, the essence of the human spirit.

With this universal backdrop in place, one particular moment stands out in the piece. It is an early foreshadowing to the climax found later on, a musical parallel that, like the early ripples of a wave, slowly builds up for the final crescendo. In it, the coro calls out in ardour, “o mia patria / si bella e perduta” (oh my homeland / so beautiful and so lost!) It is this explicit frase that sums the spark ignited by the song within its audiences, and that so strongly resonated with their own circumstances.

This reverberation must be contextualised to the year of Nabucco’s premiere, 1842, for it saw the budding of a national idea within the Italian people: the Risorgimento. The roots for the Risorgimento had started spreading in the 1820s, and, by and large, it was the desire to unify the different states into the Kingdom of Italy. Cogs had been spun into motion with the downfall of Napoleon, and the reconstitution of European political order. Soon followed revolutions from Austrian rule in the 1860s, culminating in 1871 with the complete unification of Italy.

It is, therefore, no wonder that audiences responded with nationalistic fervour to the themes of longing for an estranged homeland. In fact, myths formed that, at the premiere, audiences demanded an encore, an incredibly significant gesture in opposition to Austrian decrees that forbid encores at the time. While this myth has since been proven unfounded, “Va Pensiero” did strike a chord within the Italian people that was not soon dispelled. Regardless, simply by virtue of its propagation, the myth of the encore emphasises the impact the coro had on its audiences. Over the years, it came to be considered the anthem of the Risorgimento, and Giuseppe Verdi came to be regarded as a musical figurehead of the Italian unification – in association with the other leading Giuseppe: Garibaldi.

As the coro reaches its apogee, they appeal for the strength to bear their suffering in virtue. This is perhaps what gives “Va Pensiero” its struggente, poignant power: the resolve to rise above the greatest of hardships, in the face of utter loss, for the sake of one’s faith. It is something that goes beyond mere national identity or patriotism, or even national loyalty, but a belief that even in the worse of times, righteousness will prevail. It is, in fact, the essence of the human spirit.

With this universal backdrop in place, one particular moment stands out in the piece. It is an early foreshadowing to the climax found later on, a musical parallel that, like the early ripples of a wave, slowly builds up for the final crescendo. In it, the coro calls out in ardour, “o mia patria / si bella e perduta” (oh my homeland / so beautiful and so lost!) It is this explicit frase that sums the spark ignited by the song within its audiences, and that so strongly resonated with their own circumstances.

This reverberation must be contextualised to the year of Nabucco’s premiere, 1842, for it saw the budding of a national idea within the Italian people: the Risorgimento. The roots for the Risorgimento had started spreading in the 1820s, and, by and large, it was the desire to unify the different states into the Kingdom of Italy. Cogs had been spun into motion with the downfall of Napoleon, and the reconstitution of European political order. Soon followed revolutions from Austrian rule in the 1860s, culminating in 1871 with the complete unification of Italy.

It is, therefore, no wonder that audiences responded with nationalistic fervour to the themes of longing for an estranged homeland. In fact, myths formed that, at the premiere, audiences demanded an encore, an incredibly significant gesture in opposition to Austrian decrees that forbid encores at the time. While this myth has since been proven unfounded, “Va Pensiero” did strike a chord within the Italian people that was not soon dispelled. Regardless, simply by virtue of its propagation, the myth of the encore emphasises the impact the coro had on its audiences. Over the years, it came to be considered the anthem of the Risorgimento, and Giuseppe Verdi came to be regarded as a musical figurehead of the Italian unification – in association with the other leading Giuseppe: Garibaldi.

Yet neither the composer nor the coro had had political ambitions. While Verdi did take on political positions later in life, at the time he composed Nabucco his concerns revolved around the art of opera, and if the song struck a chord, its power was more perchance than by deliberate design. The laden socio-political meaning of the song was in fact only retrospectively attributed. As such, it serves as an example of the power of art to inspire sentiments within people. By stirring emotions within the audience, “Va Pensiero” was adopted by the Risorgimento movement as a spearhead through which to legitimise their mission. Its themes reflected the emotive psyche of the nation, and its rousing music and lyrics exalted feelings of longing to celestial scales.

When Verdi passed away, Italy had been unified for thirty years. At his funeral, a crowd of 300,000 broke out in an impromptu performance of “Va Pensiero,” under the conduction of a young Arturo Toscanini. Since, appeals have been numerous for the replacement of the Italian national anthem with “Va Pensiero,” proving its contemporary relevance still holds for the Italian nation. So, before the triumphal trumpets of Aida, before the rustling waltzes of La Traviata, came the longing of the harp chords of “Va Pensiero” in Nabucco. Not intended as anything but a diegetic moment within a story, it however proves the pervading power of art to stir within audiences emotions of a far greater scale. It proves the power of opera as an influential theatrical genre. It proves the emotional mastery of Giuseppe Verdi.

Yet neither the composer nor the coro had had political ambitions. While Verdi did take on political positions later in life, at the time he composed Nabucco his concerns revolved around the art of opera, and if the song struck a chord, its power was more perchance than by deliberate design. The laden socio-political meaning of the song was in fact only retrospectively attributed. As such, it serves as an example of the power of art to inspire sentiments within people. By stirring emotions within the audience, “Va Pensiero” was adopted by the Risorgimento movement as a spearhead through which to legitimise their mission. Its themes reflected the emotive psyche of the nation, and its rousing music and lyrics exalted feelings of longing to celestial scales.

When Verdi passed away, Italy had been unified for thirty years. At his funeral, a crowd of 300,000 broke out in an impromptu performance of “Va Pensiero,” under the conduction of a young Arturo Toscanini. Since, appeals have been numerous for the replacement of the Italian national anthem with “Va Pensiero,” proving its contemporary relevance still holds for the Italian nation. So, before the triumphal trumpets of Aida, before the rustling waltzes of La Traviata, came the longing of the harp chords of “Va Pensiero” in Nabucco. Not intended as anything but a diegetic moment within a story, it however proves the pervading power of art to stir within audiences emotions of a far greater scale. It proves the power of opera as an influential theatrical genre. It proves the emotional mastery of Giuseppe Verdi.

Design by Giulia Cristofoli

Do you want to double-check the information you just received? Here are the sources the writer used.