An Ode to MGM

‘Frothy confections’ is a term that’s often heard to describe early movie musicals of the 1930s. True, if one considers them from such a perspective, that’s all they’re bound to see. Mindless entertainment, for likewise mindless masses, may not appear particularly artistically affluent. Nor does it strike as greatly relevant anymore. Yet a closer look reveals the pervading influence they still disseminate today. More importantly still, it reveals their profound beauty and artistry, explaining their continued appeal in a time removed from their creation.

The movie musical par excellence entails a number of prerequisites, of which we choose from the cream of the crop. Firstly, for it to be a musical there must be music. Cole Porter proffers himself for the lyrics, which are invariably witty and worldly; Dorothy Fields instead volunteers for the music, always abounding in life-affirming gaiety. Next, the dancing: Busby Berkeley dependably choreographs a visual cascade of legs and arms. The costumes are taken care of by Adrian, turning the screen into a birdcage of feathers and sequins and ornate headpieces. What’s left now are the stars: glamorous to unfathomable extremes, they are unreachable comets from a firmament of virtuosity. Ann Miller breaks a new tap world record while Van Johnson struts, suave and debonaire. This is the MGM musical par excellence.

At the peak of the Golden Age in Hollywood, in the 1940s and ‘50s, it was the Metro Goldwyn Mayer studio that held the monopoly on the musical genre. A dazzling musical extravaganza a year was its unspoken promise. Yet in the early days of the 1920s most studios produced musicals, and several a year at that.

Despite this great demand, such films were denigrated by the intelligentsia as demonstrative of the ‘worst’ of American culture. Figures like Adorno and Horkheimer, or Siegfried Kracauer, appointed themselves critics of culture, and saw these films as the instruments of cinematic oppression towards the masses. The danger lay in the ability of these glamorous dreams to fill an unconscious void in the ‘numb’ masses, rendering them hopelessly passive in a self-perpetuating cycle of commercially-driven indoctrination. Likewise, those of the general public with more conservative minds, viewing musicals as decadent displays of lust and vice, considered them indecent and morally degrading. Going to the theatre and the cinema, after all, was still a choice of dubious character, in some circles.

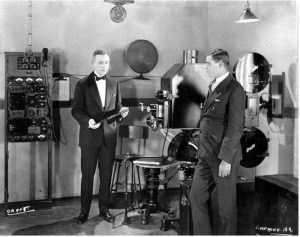

These opinions however derived from the greater socio-cultural context of the time. Movie musicals emerged in the late 1920s through the long-awaited development of sound recording technologies. Thus the birth of movie musicals coincided with a time of punctured hopes and deflated expectations, as the stock market crash ended the prosperity that characterised the Roaring Twenties. The national mood was one of depression, and escapism was needed, and found, through musicals. For a few cents, audiences could be transported into an ambience of elegance and refinement, where good invariably trumped over wrong at a foxtrot tempo.

Gene Kelly’s elaborately choreographed stories were still a few years in the making at this point, however. The first movie musicals were veritable tableau vivant: incredible visual feasts of scenic designs served as backdrops for ornate movements of chorus girls. The camerawork was static – almost stiff, as testified by instances of jerky pan shots caused by too-tight tripod mounts. This came as a consequence of the new genre, for which the medium still had to acclimate: directors and cinematographers did not know how best to capture the larger-than-life spectacles through the advantages of the cinematic lens. What resulted were photograph-like images of what were essentially shows designed for the stage, much in the style of the Zigfield Follies.

In fact, the Zigfield Follies started a chain reaction in forming the identity of the musical genre. The development of the stage musical had started in the mid-1920s, evolving from the revue. Through the contemporary developments of linear storytelling in Hollywood, Broadway came to redefine its narratives as well. As such, film and stage came together in a cheek-to-cheek to mature the genre. Storylines developed from disjointed scenarios to narratives where song was integrated as a vehicle through which to continue the story’s development. The logic, by the early 1940s, was that a song was but a continuation of the characters’ dialogue, which, having reached its emotional peak, had to burst into a form of communication higher than the mere spoken word.

Masterful pirouettes, nimble footwork, exuberant costumes, passionate singing – glamour, in fact

Concomitant to the development of storylines, the cinematic eye widened its eyelids as well. In an almost inconceivable turn, the camera became as much a participant as the actors and actresses, and the action thus became more mobile. Audiences were immersed into the illusion of reality through movement and action, once the static sets from the Broadway stage were discarded. This was in particular the achievement of choreographer Busby Berkeley, who simply choreographed the camera into the dances as well. His trademark came to be the ‘flower shots,’ where chorines joined in kaleidoscopic formations and were filmed from above, creating visual doilies. Berkeley’s imagination knew no limits: his camera flowed between the legs of chorines or glided back and forth to reveal masses of dancers or the tapping toes of a star. His chorines danced as fountains, danced on gold coins or pools, and, above all, danced on stairs.

The stairs in fact came to be one of the most indelible images of movie musicals. Incredible heights of glamour flowed from the screen at the sight of a star, decked in sequins or see-through gauzes trimmed in ostrich plumes, as she descended stairs in devastatingly light steps at the downbeat of her dance number. Judy Garland, Ann Miller, Eleanor Powell, Cyd Charisse – even Shirley Temple – all descended stairs. Perhaps it was a visual representation of the ‘stars’, these deities, reaching us common mortals. Perhaps, and more likely, it gave actresses a purpose during the delivery of their songs. Regardless, it became a staple.

Likewise, numerous other conventions of the musical genre became staples, and have remained so to this day. There are boundless examples in everyday culture, cinematic and not, of the impact left by the musical genre, to an extent where it would be a pedestrian effort to list them. Masterful pirouettes, nimble footwork, exuberant costumes, passionate singing – glamour, in fact – still remain appreciated today, despite a distance of almost nine decades. One just needs to look at the views of the mashup video of MGM musicals to “Uptown Funk” on YouTube, and they’ll be assured of the staying quality of classic movie musicals. So although movie musicals were frowned upon, they have left an indelible mark, transforming past guilty pleasures to benchmarks for contemporary culture.