Accidentally revolutionary

There is no better way to describe Tropicalismo than as a casual conversation with friends that became an artistic movement. It started with the intention of discussing the modernization of art. It was just an unpretentious gathering of people who truly needed a space to talk about their artistic ideas, to think together on how to move Brazilian modern art forward. And just like that, the most influential movement that would change Brazilian music – and the country’s future – started.

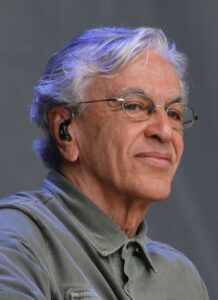

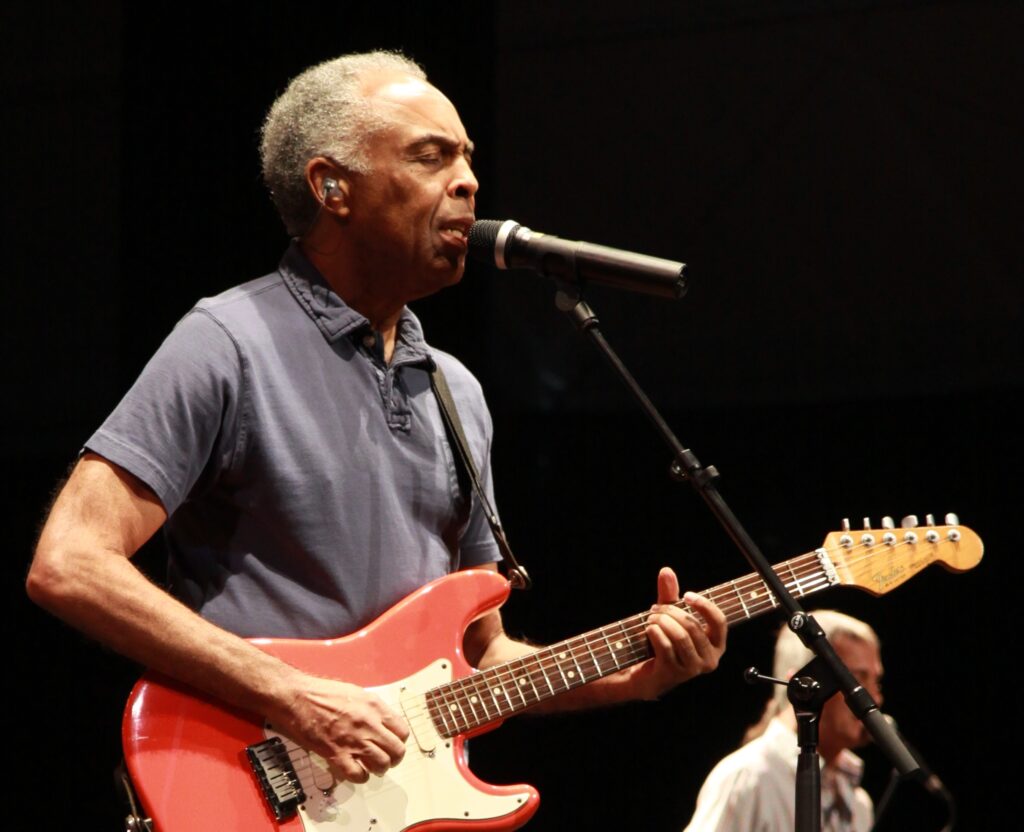

It started in 1967. After what had been a weird decade – with the Cold War, the division of the world, the rapid rise of the media – artists were confronted with a complex environment full of fragmentation and reevaluations of the previously stablished order. So, it was in 1967 that Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil went on the stage of a Popular Musical Festival and sang something that was everything but the nature of Brazilian popular music (MPB). It was singing “Alegria, Alegria” and “Domingo no Parque” that the two musicians casually started their polemic Tropicalismo. For the first time they were incorporating an electric guitar! If you are thinking ‘and so what?’, I will ask you to pretend, for a second, to be abismado and bear with me a little. It was also the first time that the lyrics presented implicit messages, complicated metaphors and a structure that resembled more concrete poetry than general music lyrics. And did I mention that all of this was broadcasted on national TV? The terrors of the avant-garde had finally reached the traditional middle-class household.

The electric guitar and innovations in lyric construction were only a symptom of the singers’ ideas. Their goal was to create confrontation and make polemic statements through music. Searching from references outside the Brazilian territory, the artists of the movement introduced an international context to the national landscape. Of course, Veloso and Gil, coming from a culture of Bossa Nova and other genres that had characterized Brazilian music, didn’t leave their origins behind. They united contemporaneidade e tradição. To put in today’s terms, what they did was like putting pineapple on pizza: an outrageous practice for traditionalists of the Italian cuisine, agreeable for the modern palate that seeks the unconventional bittersweet.

Bittersweet was actually the general taste they left in the mouths (or ears) of any Brazilian who heard their songs. Presenting fragmented images of the Brazilian reality, they mirrored a society that was under a ditadura militar, with an ever-growing, effervescent counter-culture, mediated by the explosion of mass communication channels. It was a lot. Brazil in the ‘60s and the Tropicalia movement together: it was a lot.

In their essence, the artists of the movement held an ironic attitude towards everything. Desacralizing: the album that epitomized their work was the album Tropicália ou Panis Et Circencis. Just as provoking as the title are the lyrics of the songs. It is a sort of collage of the different aspects of the country’s social characteristics but in a very sneaky way. They had to be. The growing pressure of censorship under the ditadura forced them to subtly present their controversial ideas.

But while their lyrics were nuanced, their behaviour was the exact opposite. Their behaviour ranged from the classic direct response to the audience to appearing pointing a gun in your own head during a Christmas TV show. Let me give some context. Among so much controversy, Gilberto and Caetano managed to get a TV show which they entitled Divino, Maravilhoso (Divine, Marvellous). In there, they performed all kinds of weird stuff, with the goal of outraging anyone who was watching it. It started simply: Caetano plantando bananeira, standing upside down, in the middle of a song. Then it got more experimental, with the same figure locked in a cage. After that, it got controversial when Gilberto Gil embodied Jesus in a supper with a lot of bananas. It ended outraging with Caetano singing a Christmas song with a gun pointed to his head two days before Christmas. I’m not sure why, but after that, they were imprisoned, the show was and the artists only walked on Brazilian streets again in 1972.

Their attempt to outrage audiences surely worked. The reactions to their songs were quite vehement. Tropicalismo was considered sometimes immature, sometimes just emptily trendy, but the critics always reinforced the idea that it was something that wouldn’t last. Even the notorious Augusto Boal (a theatre practitioner that created the concept of the Theatre of the Oppressed) thought that the Tropicalismo attacked the wrong people; it was inarticulate; it was too gentle and just another movement to please the bourgeoisie.

While Boal’s discontent relied on the idea that Tropicalismo wasn’t radical enough, others criticized it for its subversion. What was so revolutionário about their practices was that they weren’t afraid to contest the status quo during a government that had its entire ideology based on that same status quo. But the conservative ways of viewing society didn’t fit the lived reality. So, what these artists did was refurbish the allegories that characterized the country so that Brazil could rediscover itself. It was seeing the uprising and social agitations of the time that led the government to decide in 1968 to end civil and freedom of expression rights. The movement died out without its main representatives on stage, but not without leaving a permanent mark in the Brazilian cultural landscape. It was thanks to their bravery that the people started to realize that they lived “among pictures and names, without books or rifles, without hunger, without phone, in the heart of Brazil” (my loose translation of “Alegria, Alegria”).

Tropicalismo is what reintroduced culture syncretism in Brazilian culture, creating this rich and intrinsic world that we think of today when we think of MPB. They also introduced Brazil to the world – well, Gilberto and Caetano couldn’t play in Brazil, but the militares couldn’t control them elsewhere. They presented a harsh reality and gave voice to a counterculture that was tired of the hegemonic imposition of an unstable, conservative, and authoritarian government. They became musical icons. And symbols of resistance. Their exile was just the proof of an intolerable ditadura. Yes, it took another 16 years for the political system to change. But they planted the seed of doubt into people’s minds, exposing them to the previously unimaginable. They were the friendly artsy conversation that spread their wings and, in all honesty, allowed Brazil to fly, even when its wings were cut down.

Designed by Giulia Cristofoli

Do you want to double-check the information you just received? Here are the sources the writer used.

http://tropicalia.com.br/

https://g1.globo.com/pop-arte/musica/noticia/2018/08/07/tropicalia-ou-panis-et-circencis-completa-50-anos-conheca-os-bastidores-do-disco.ghtml

.