The 19th century is known to be one of social awareness. Especially in France, the condition of the lower classes began to interest artists. Lots of writers choose anti-heroic protagonists to depict the society of their time. It was not the first time that middle and lower classes were being represented, of course, but, in this period, it was taken to another level.

In painting, this interaction of classes took the form of realism and one of the modernist painters’ theme of predilection was the representation of sex workers.

Women are omnipresent throughout the history of art but their representation has changed over time. Before the realism we mentioned was introduced, naked women could be seen only if they were embodying goddesses or muses. The feminine body was always highly idealised to concur with the aesthetical codes of the time.

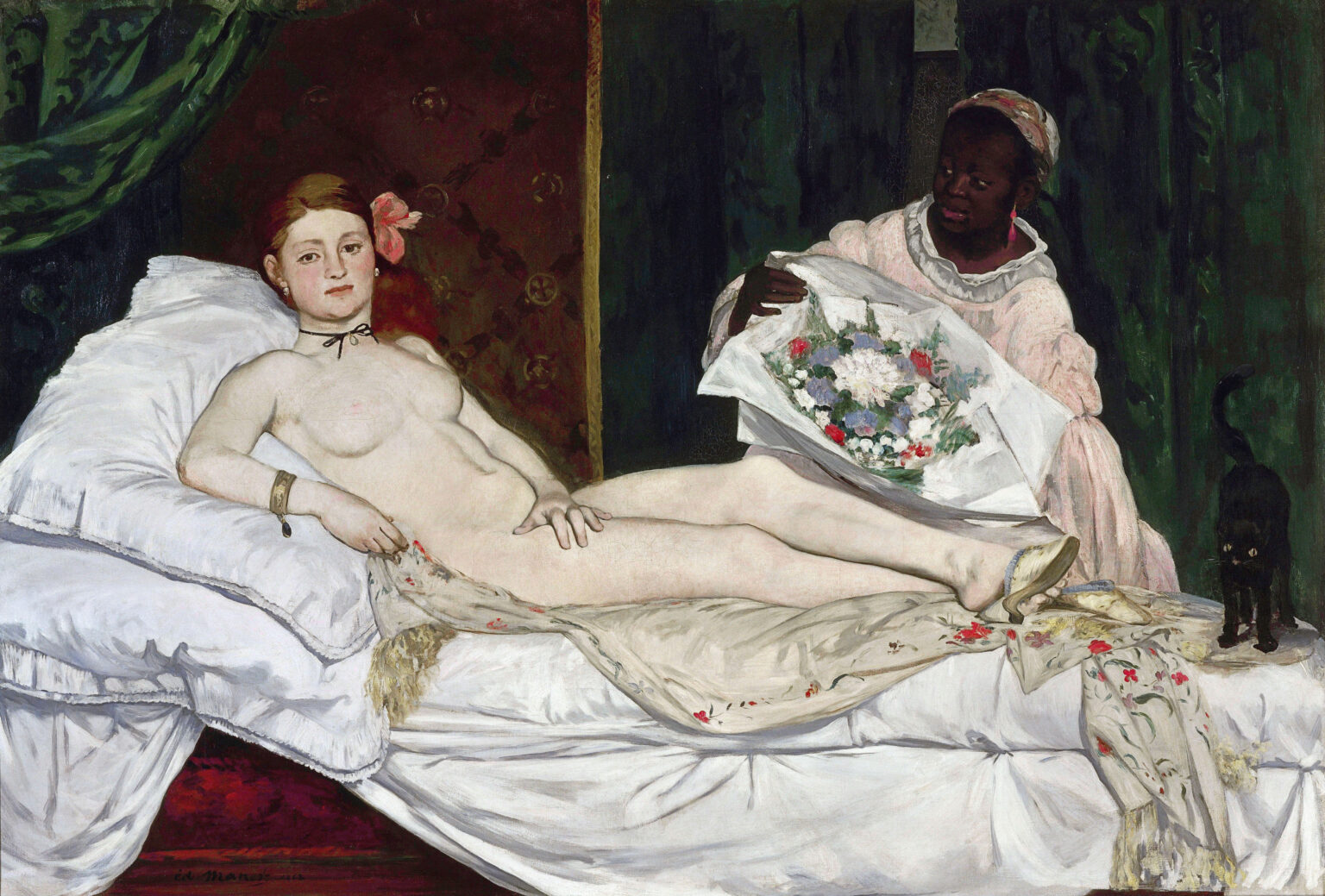

And then comes Manet. So, in 1965, Manet’s work called Olympia was presented at the official Salon in Paris. At the time, it was the place for artists to be seen. If you know the painting, you’ll see what I’m getting at. If you don’t know it, it’s even more interesting. Ask yourself: what could be shocking here? Because, believe it or not, this picture created an absolute scandal.

A little earlier, The Birth of Venus by Cabanel was exhibited and had a real success. Both paintings represent a naked woman lying on the sea/a bed, right before the viewer’s eyes. The difference being that one is a Greek goddess, the other is a woman you could meet on the street. Even more so, she is a sex worker. The society of the 19th century was very aware of the existence of prostitution and brothels, but one wasn’t supposed to talk about it and even less show it in a painting that is not small at all. Manet painted her almost the size of an actual woman, one who could remind some gentlemen of their own mistresses. Imagine walking into the room and meeting with the unofficial companion of your nights, revealing herself among other Venuses.

Olympia is staring at us, almost provocative. She is the vessel through which the artist questions the viewer about the society of the time. The bouquet of flowers is the hint revealing what is going on: it was probably sent by a client. She is for sale and that’s a reality people didn’t want to see. It represents the commercialisation of a human being to respond to a certain desire.

However, Manet doesn’t paint any sex worker; he paints what we call a “courtisane”, whom are on top of the hierarchy of prostitution. Indeed, this world was, and still is, a very coded one. These women climbed the social ladder by selling their charms and securing protectors. The courtisane is a lot about appearances. When you see her, you’re not supposed to see someone selling herself but rather a seductive young woman. That’s also why Olympia has shocked: she is revealed in the full meaning of her condition.

They held famous salons much appreciated by the elites that were mondain events where selected people would gather to have intellectual conversations and to bond with the finest people. And, actually, they helped a lot with the emancipation of women.

Courtisanes were able to speak their minds, to be libertines; they influenced fashion, arts, and even politics. Some of them were well-known for their career on stage. You might have heard of Sarah Bernhardt, the theatre actress, who was extremely famous in her time in France but also in the US. Her portrait by Georges Clairin (1876) very well illustrates the situation of the women called demimondaines. In this portrait, Bernhart is seen in her private mansion which she had just bought at the time, on a luxurious divan covered with precious cloth and pillows. The demimondaines were also called the “grandes horizontales” which literally means the great horizontals, a nickname referring to the horizontal position they’d occupy most of the time to obtain money. A position that Sarah Bernhardt was adopting here. A waging as an actress, dancer or opera singer was no way near enough to buy a mansion such as the one we can see in Clairin’s painting. It was a way to show how influential and wealthy their lovers were. It was scandalous. But also irresistibly attractive for both men and women who often ended up imitating the fashions launched by the most famous courtisanes.

As Dumas’ novel La Dame aux Camélias (1848) explains, protecting a demimondaine was not at everyone’s reach. Only the wealthier gentlemen could afford it and when they did, they’d make sure to let everyone know who had won their heart. A courtisane had to be pretty, funny, smart and witty. So, sadly, after they beneficiated of ten or fifteen years of luxury, they often ended miserably. Once their beauty faded, lovers turned away and took their money with them. It is more or less the lesson that nothing ever lasts.

These three examples illustrate how sex workers have been a source of inspiration for artists. When it comes to the courtisane though, she is still depicted for her beauty. There is a sense of idealisation. Maybe the muse of modern times. It’s only around the last third of the 19th century that painters, going further, diffused pictures of sex workers with all the crudity of the context of brothels, proving that these women never ceased to fascinate and that’s why artists have kept using them as models and characters.

Designed by: Nina Gueorguieva

Do you want to double-check the information you just received? Here are the sources the writer used.