A Bird of Beauty

The life of Edith Piaf, and the redemption of suffering

At first glance, it appears true beauty always eluded Edith Piaf. At just one and a half metres in height, with the slight figure of a waif, the French chanteuse was never acclaimed for her looks, and her 28-year career never rested on visual glamour. And yet, she rose to international adoration. When she raised her voice in song, the swallows returned in shame; and it was indeed fitting, since her life was so closely entwined with birds. It was birds that would prove to be the metaphor that accompanied her through life.

The true and tested cliche of rags to riches finds no better example than in the ascension of Edith Piaf, who was born to a street-singer mother and street-acrobat father at the height of the First World War. Her father was in fact fighting at the front when her mother, Line Marsa, couldn’t reach the hospital in time to give her birth. Edith Giovanna was thus born on a December sidewalk in the Menilmontant neighbourhood of Paris.

Upon returning from war, Louis Gassion, Edith’s father, found his wife fighting an impossible battle with alcoholism. To save his daughter, he brought her to stay with his own mother, a madame who ran a brothel in Normandy. There, Edith was to spend the first years of childhood surrounded by a plethora of mothers, in the absence of her own. It was also there that from the ages of five to seven she was blinded by a severe case of conjunctivitis. Once cured, her eyes could no longer shield her from her depraved surroundings, so her father took her back with him, to perform on the streets.

By age fifteen, she was living by herself, earning a living by singing on the trottoirs of the poorer districts of Paris. A first love left her with a child at seventeen, but the little Marcelle died two years later from tuberculosis, leaving a wound that never healed for Edith.

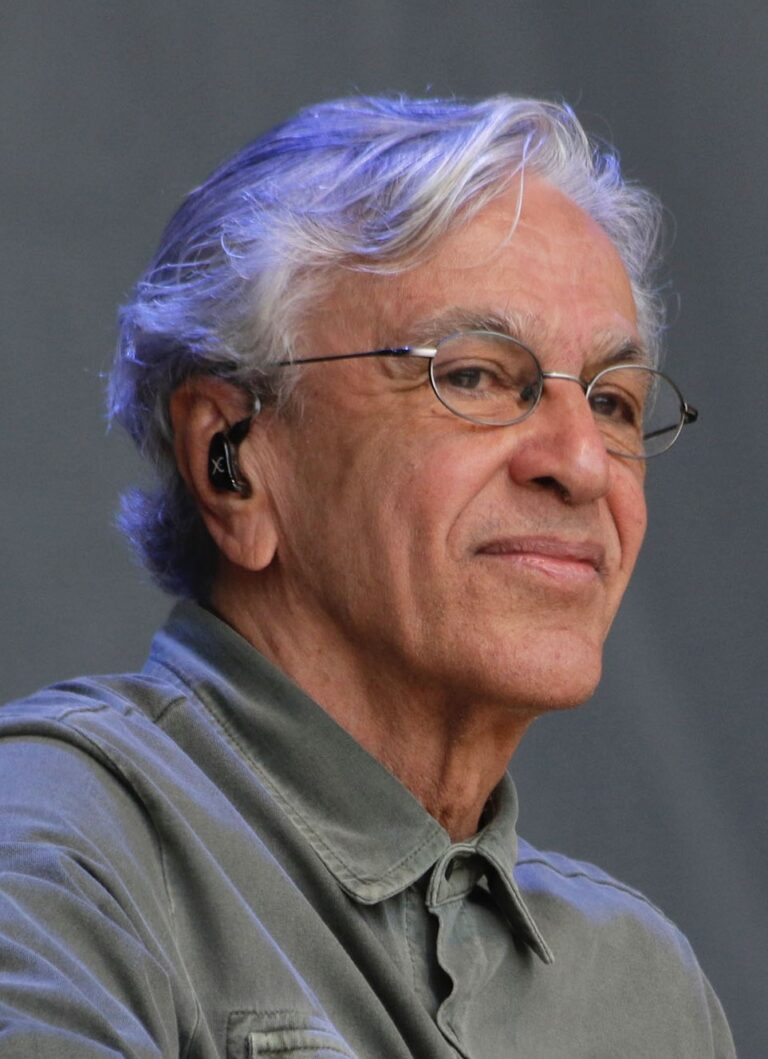

It was a chance meeting that led to the first bird figure in Edith’s life. A cabaret impresario recognised a glimmer of talent in this street singer with the bold demeanour emanating from a fragile frame. He invited her to a milieu of darkness and spotlights and microphones, finally leaving behind a start to life comparable to Victor Hugo’s Cosette. The harsh lifestyle she had been leading formed Edith into an emaciated figurine, with dark frizzy hair, large eyes, porcelain skin and delicate fingers. Recognising the need for a name of artistic stature, piaf was chosen from the Parisian argot’s appellation of sparrows, reflecting her humble appearance. Edith would be no swan, no peacock, but a sparrow.

Much of Edith’s artistic persona was developed during these early years of her career. The chanson réaliste was at the peak of its popularity, with names such as Damia, Frehel and Marie Dubas despairing in songs of destitution, hopelessness, and the colourful lives of figures who lived on the fringes of society. Such themes were carried throughout her career’s repertoire, which had a pronouncedly dark tone.

This profound sense of unfulfilled longing rendered her voice recognisable. It was a voice marred by devastation, but which one could sense had risen time and again above the afflictions of life, from the power it emanated. Her vibrato, phrasing, and that unmistakable trill of the R letter, soared over any obstacle they encountered, and declare life before all.

It was from studying Damia in particular that Edith developed her performing sensibilities, recalling the visual impact of a simple black dress set against a dark stage, with only a spotlight to illuminate and concentrate all attention on the singer’s face and hands. This striking chiaroscuro became the driving idea behind all her performances. She would not enrich her modest visual persona a la Mistinguett or Josephine Baker, with beads and feathers abounding. It would be singing distilled into its purest form, no visuals to disguise or embellish. It would be her voice alone to reign supreme on the stage.

One of her most recognisable trademarks was an almost severe sense of austerity, from her wardrobe, to the ensemble. Although items from major maisons de mode were plenty in her closets, it was that simple black dress with which she became almost synonymous. Variations on it reflected changing fashions through the years, starting first with a buttoned-up shirtwaist, which morphed into a comfortably open shirt collar, ending finally with the triangle décolleté that was to accompany her final performances. The choice of this little black dress also reflected the times during which her career blossomed – the Great Depression. She would thus also make a statement in wearing a dress that was simple and accessible to women of all social classes, staying true to her frugal origins and not buying into meretricious styles. On several occasions she explained she started by singing on the streets, and that moving to more sophisticated circles would simply not do for her.

Her first of many tours in America also proved to be another decisive moment in the assertion of her artistic identity. The exoticised expectations of American audiences were left aghast when they did not find Edith prancing on the stage with a lineup of can-can girls, as might have been the case at the Moulin Rouge. They were instead met with a diminutive figure who stood solidly in front of the microphone, a near black and white image shattering Technicolour palates. Her hands would move in deliberately expressive gestures, but would find frequent resting places on her hips, letting her voice alone enchant the audiences. There were no chorus girls or boys, but instead a smattering of musicians huddled in a corner: a guitar, a bass and an accordion gathered around a piano. Critic Virgil Thomson was the first to recognise this form of spare beauty, Edith’s stature as a great technician because she employed the simplest of methods to the greatest effects.

It was with this recognition that she became the representative of French music, and indeed, France itself. Her voice was heard the world over, both on record and live, with several tours stretching from central Europe to South America. She appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show an unparalleled eight times, sang at Carnegie Hall twice, and held strong positions on song charts. By the mid 1950s, she had become one of the highest-paid entertainers in the world.

Yet, as her career flourished, and the world came to revere this unlikely star, her personal life never seemed to leave behind the shadows of the slums. Her major love died in a plane crash, leaving Edith in a strenuous period that resulted in a dependance on medications based on morphine. She developed an addiction that would plague her for years to come. She survived four major car accidents, which however also left their mark on her precarious health. By the end of the 1950s, she had endured major operations, frequent stays in hospitals, and even more frequent collapses on stage. The intensity by which she lived life drew poetic comparisons to a candle burning at both ends. Several times doctors forbade her to continue performing. But singing on stage was the ultimate necessity for her. She often stated in interviews that if she couldn’t sing anymore she would commit suicide, “puisque chanter c’est ma vie,” since singing was her life.

By 1960 she had lost all powers, following what the press baptised ‘la tournée suicide’, and was forced to convalesce most of the summer. It is at this point that the second major bird figure arrives in her life, however acting as an ominous bookend. Worn out, weighing less than forty kilos, suffering from an aggressively destructive form of polyarthritis, and having almost lost her voice, it seemed Edith would not perform again. And yet she was resuscitated like a phoenix by a song that was proposed to her.

A lilting melody played by a harp, set to simple but deliberate lyrics on the theme of survival, “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien” came to symbolise her whole life. It was this song that gave her the strength to return on the stage, for major engagements at the most prestigious French music halls. For the next three years until her death she sang this song in defiance of the illnesses that plagued her. Her hands, clenched shut by arthritis, could open on the stage as if by magic, giving back her expressive mastery. She would walk on the stage with a fragile gait, stand even more hunched than before in front of the microphone. By the end of performances her hair would be matted in sweat on her large forehead, called virtuously pathetic by Jean Cocteau.

Her voice had lost much of its power and crystal clarity. At times it seemed thin for air, and forced her to sing in a lower register. And yet she sang, and the ovations were never greater. The beauty of her voice resuscitated her, and still enchanted audiences. This beauty came from her herculean strength, which itself was derived from suffering. Strength and suffering thus formed a co-dependence that allowed her true beauty to shine. This pathetic sense of tragedy, contrasted to her defiance, was what appealed to audiences. Charles Aznavour, one of her many proteges, explained that “she was never so adored as when she was almost dead… French audiences love the goût de malheur.”

During this time she was asked if, when she sang, she thought of anything in particular. She explained that a lot of her songs were on the theme of love. As such, in her mind she would “create an ideal being that however doesn’t exist.” And yet from this inspiration came her signature style of beauty that still pervades the musical world today.

Design by Giulia Cristofoli