Vissi d’arte

The socio-artistic demands of opera

Few are the art forms as linked to tradition as opera. Embedded within a rich history of conventions and techniques, opera’s life spans over five centuries and spreads across Europe. As though captured in amber, today it provides us with a breathing, vital link to the men and women of a bygone era. In fact, it’s a testament to socio-cultural tastes – tastes that are, however, intrinsically tied to the past. It is thus not surprising that since the revolution in popular music in the 1950s, the popularity of opera has wained, and continues to do so to this day. Be it for its artistic qualities, or the ideology it perpetuates, it seems to not hold as strong a resonance as it did during its peak of popularity, in the nineteenth century.

One such reason for this stagnation and recession can undoubtedly be found in the form of the genre. Moving past the musical style, governed by melody and harmony, it is the presentation of opera that nowadays is most objectionable. Heightened emotions are expressed in wide, larger-than-life mannerisms and poses that seem contrived and artificial to modern palates. But this is entirely intentional since form follows content, and immense emotions must be expressed with immense gestures.

This greatness of scope is also dictated by the subject matters dealt with within opera. As dramas, they focus on the human state, and recurrently deal with love, betrayal, family, murder and death. Take Verdi’s La Traviata, unarguably the most revered piece in opera repertories; its plot revolves around a dying courtesan condemned to be separated in love by an unwavering society. Depicting the immense scope of emotions asked for by the story and captured by its music, would be absurd in the minute styles of method acting, or of television directing. Verisimilitude to life is left aside for a greater exaltation of the human condition, reaching almost the religious heights of the sublime, for an experience that elevates audiences to unquestionable Bildung.

It is on this point that opera diverges so strongly from contemporary expectations, which demand that genuine lives and characters be depicted in true-to-life manners. Egalitarian calls for casting of actors within the performing arts are today governed not so much by talent but by the degree to which an actor or actress best reflects the ‘group’ of the character: their race, sexuality, social class… At a growing speed, the craft of acting is being overtaken by ‘being,’ overshadowing the purpose of acting altogether, which is in essence the act of portraying and embodying someone other than oneself. This is the natural result of a society consumed with the quest for equality, no matter how far this encroaches on the autonomy of the arts. A perusal of recent premieres confirms the general appeasement tactics taken by Hollywood studios, in particular regard to franchises (such as in the Marvel or Star Wars universes).

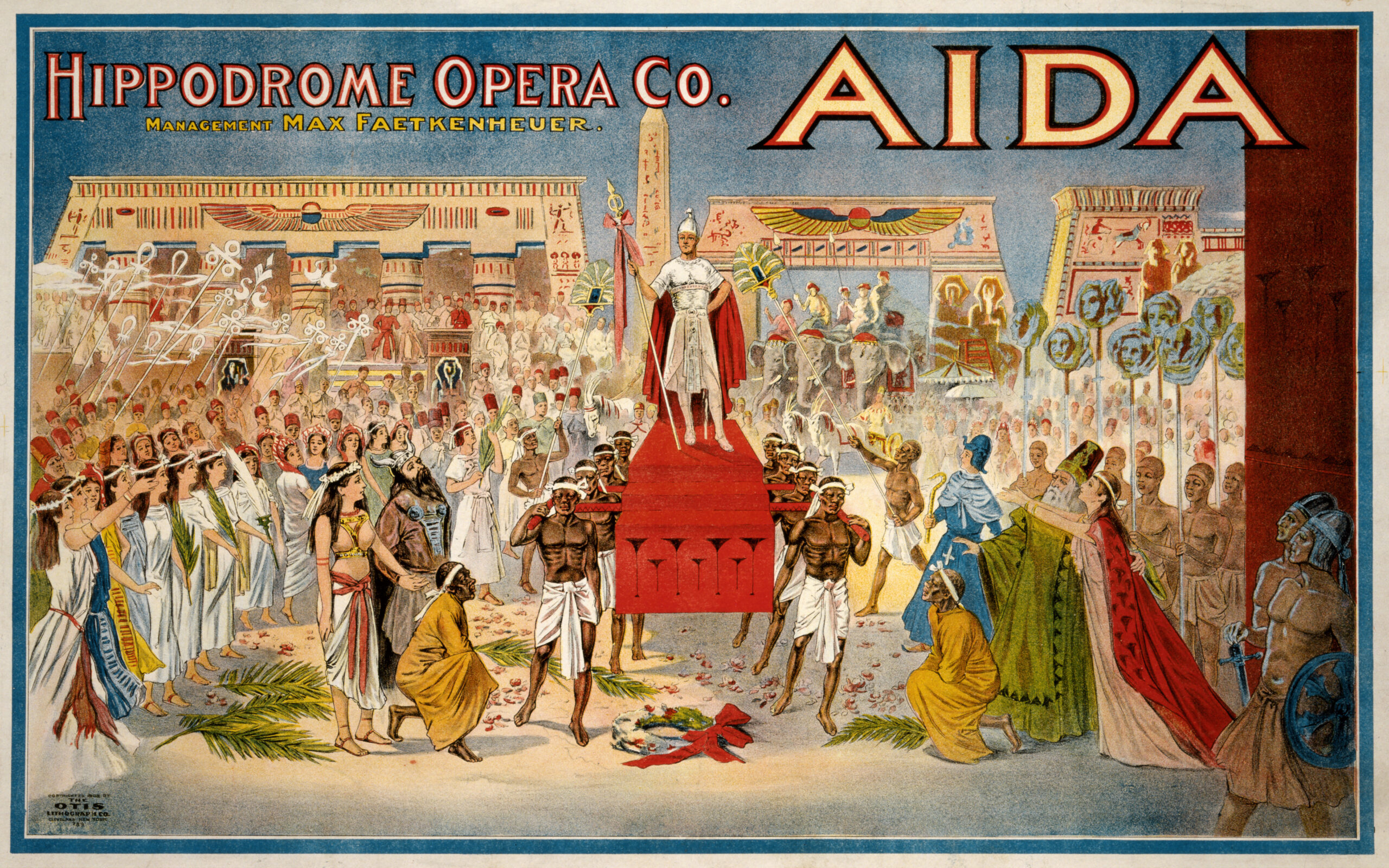

Yet during the heyday of opera, in mid-nineteenth-century Italy, France and Germany, this was a lesser concern, and what was foregrounded was indeed excellence in the art form. What this resulted in were practices that by today’s standards are frowned upon. Portrayals of ethnicities other than one’s own, were, for example, dictated frequently by necessity at a time where globalisation and internationalism were not the norm. The eponymous characters of Aida and Madame Butterfly were portrayed by European actresses, and still are so today at times. Naturally, Ms Leontyne Price proved an excellent choice as Aida. Notwithstanding, who could argue against Greek Maria Callas’ Japanese Cio-Cio-san? And who could reject Italian Franco Corelli’s Egyptian Radames? In such cases, it is not so much a matter of ethnicity, as a matter of artistic competence, that reigns supreme in an art form that elicits such fervent and passionate expectations in its audiences.

Perhaps a greater still contestation emerges in opera; this time, it is not brought by today’s ‘woke’ society, but is a point of conflict between opera lovers themselves. It is the question of age. It is frequently the case that the vocal demands made upon singers are too elevated for youthful newcomers, and consequently casting leans towards more mature actors and actresses. However, there are certain roles that should logically be played by more age-appropriate singers, as dictated by circumstances. It would stand to reason that the aforementioned lovers in La Bohème should be played by singers in an age close to university students in their twenties. More often than not, they are instead portrayed by more mature singers. This is because the voice of a twenty-year-old simply cannot compare with the experienced and richly-tuned voice of a thirty or even forty year old. Operatic voices are built over years of experience, performance, and study, regardless of natal gifts. So then the question is whether it is preferable to hear “Che gelida manina” sung with the vocal prowess and emotion of an accomplished singer or to see Mimi and Rodolfo as two young university lovers.

Likewise, it so frequently occurs that characters who are by definition svelte and beautiful, such as a Carmen or an Aida, are in fact played by singers who are matronly and dowager. One further reason for this disregard for age is the requisite imposed by the theatres in which these operas are performed, often colossal palaces of music. A sprightly Aida at the Arena di Verona would vanish, but Leyla Gencer instead commands presence and emanates persona. Opera singers have to be statuesque, if they want to rise to the standards set by the scale of the genre.

For these reasons, there are greater calls made upon the audience for the suspension of their disbelief, in that they should look over certain facts in order to see a greater, more artistically-elevated unity. As Wagner argued with his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, opera is the culmination of all artistic disciplines, and consequently, it is not only the artists, but the audience too, that must contribute to the creation of this whole. Audiences therefore look past the buxom appearance of a Montserrat Caballé, arguably more appropriate as the matronly Ezucena than the demure Leonora, in La Forza del Destino: they bask instead in the utter glory of her voice.

Such a progressive mindset from such an antiquated art form shows in fact there is more to be learned for today’s appreciation of casting choices. Naturally, it is easier to suspend one’s disbelief in the theatre than it is in films or television, due to the greater power of imagination held by audiences, but imagination still remains the key ingredient in the consumption of performance media. When all aspects surrounding a medium are so devoted to one goal – in the case of opera, the glorification of music and voice – there is a greater impetus to negotiate. Such is the power of opera, to overlook physical coordinates and instead reap in the plentitude of art, pure and simple.