The Vulva and the Arts

by: Giulia Cristofoli

When I set myself to research the representation of the female genitalia in the art world, I was ready to find obstacles. It is nothing new that the topic is taboo and it has been for a long while in the Western world. So, my expectations were low.

I used an academic research tool first. I typed two key terms: ‘art’ and ‘vulva’. I wanted to see what was out there by being vague (or so I thought). 22 results appeared on my screen, mainly from the medical field. Then, I went for ‘vagina’ and ‘art’. There, I got some more results, which is interesting because we apparently can still not differentiate a vulva from a vagina. But ok. Most of the results I found were about a postmodern feminist approach to performative art. And so, I dug deeper. This could not be it.

I decided to just throw it on Google. If the academic world hasn’t taken an interest in the topic, I thought the popular consensus might give me something. Indeed, I found a quite informative Wikipedia page on the subject. There was one thing that struck me though on this page: there was a major gap between the 12th and 20th centuries, except for the brief mention of Courbet’s Origin of the World. And so, I dug deeper. Again.

What you have in here is, thus, a brief account of what I found and my utmost shock of the lack of material and remaining quasi-abnegation of the female genitalia. It is an exiguous part of what I found to be a historical overview that proves that it is not the lack of artistic artefacts that have excluded our sexuality from the discourse on art, but the enormous taboo we have created around the most natural of things we can encounter in the human world: our bodies.

Symbolic representations and fertility

The representation of the body dates way further than you may think. Venus figurines date from the Paleolithic period. They are famous for their grotesque representation of the female body, exaggerating features such as breasts, hips, stomach, and – you guessed it – the infamous vulva. At the time, homo sapiens had started to carve all sorts of tools to help their daily life. But these female figures clearly couldn’t serve a pragmatic purpose. So, they are considered the first instance of art in our human history (You heard it right, the first art object is a naked woman).

Because of the idealized style in which they were carved, it is believed they served ritualistic purposes to ensure fertility. There is also evidence that suggests they were painted. The most famous of them, the Venus of Willendorf, was most likely painted in red – which might make you think of menses, but that’s just a guess, of course. This Venus receives its name by the city in which it was found: Willendorf, Austria. Researchers found that the object dates from between 30000 and 25000 BCE. With about 11 cm, this particular figurine is faceless, which only contribute to our focus on its exaggerated aspects. An idealization, without a doubt. Don’t forget that, at the time, fatness and fertility were not only praised but necessary for survival.

However, it is not set on stone that they served ritualistic purposed. They could also simply be dolls, guardian figures or just a pretty object to look at. It’s not something of which we can be sure. One thing is certain, however: they were part of the Paleolithic culture, as the vast number of female figurines outnumbers the male representations of the time (144 Venus figures found so far to be exact). Some scholars even think it might indicate that the culture of the time was a matrilineal and matrilocal one. This means that the lineage of a family is given by the mother and that the husband is the one to join the household after marriage. The Venus figures may be objects of small size, but their representation is of great power.

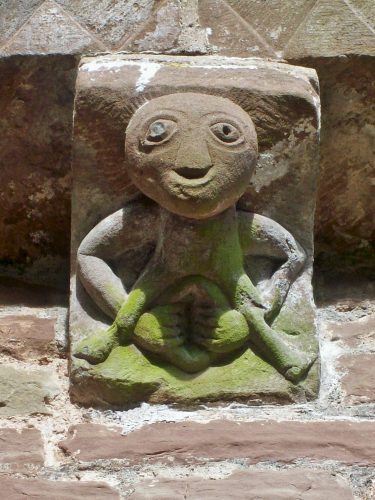

Another must-share find of the research on female genitalia is the Sheela na gig. They are bold and naked female figures that look like a little alien holding their vulva with both hands. The most impressive part is not even the explicitness of the image, but the fact that they are found in Irish, Welsh, Scottish and English medieval churches. They are not easy to find. Some have been reallocated in museums, some have been removed from their original place or modified and others haven’t been identified as such. It remains unclear what the name means. Their function varies according to communities (and researchers). It could mean a warning against sin, protective figures, a fertility goddess… The only consensus is that these intriguing figurines need further research.

The subtlety of the nude

As the tale goes, after Middle Ages, came the Renaissance. I’m going to skip the part of the innovations in painting and the Renaissance men and jump directly to what interests us: the nudes. Freeing themselves from the Church’s prescriptions (more or less) and rediscovering Ancient Greece, Renaissance artists took a wild exploration of the human body in all its magnitude.

Many artists explored both male and female nudes. They tried it on paintings, sculptures, bronzes. Titian is among the artists of the time who was quite intrigued by nude figures, portraying it in many of his works. Artists used, often, the figure of Venus to explore the theme, mixing the crudity of the naked body with an almost sacred aura of a goodness. But their attention to detail is quite oblivious of the anatomy of the female genitalia. A simple triangle in between a woman’s legs was enough for them, really.

And why is that? It’s because their goal was to portray idealized figures and showcase their skill as a painter. Besides, their source of inspiration was rarely an actual nude female body, but the works of art from the Greeks. Funnily enough, in most of the period from Ancient Greece, the vulva was censured. They loved the idealization of the male body. Females? Not so much. So, in the Renaissance, they tried their best to imitate an already inaccurate representation.

Getting modern

I’m honestly going to skip the Origins of the World bit because, by this point, we are just tired of a dead white male that made history by daring to expose a big painting of a vagina. No, Courbet was not a feminist, he just wanted to make his fellow classicist painters a bit mad because he loved the controversy of his Realism.

Another interesting figure in the portrayal of vulvas is Schiele. He experimented with nudes to try to discover himself as a painter. In the early 20th century, he painted Female Nude. This work has a striking colour use, with reds and yellows that capture your eyes way before you realize there is a naked woman there. Because of the position of the subject – a sort of mortuary figure – and the sensuality emanating from the figure’s look, it might be seen as a connection between death and sexuality. This is not the only naked figured he has made. Some of his drawings were apprehended by the police and considered pornographic. In this case, it is worth mentioning that he was imprisoned for seducing a 13-year-old girl (at the time, the age of consent was 14 years old). What an interesting character he was…

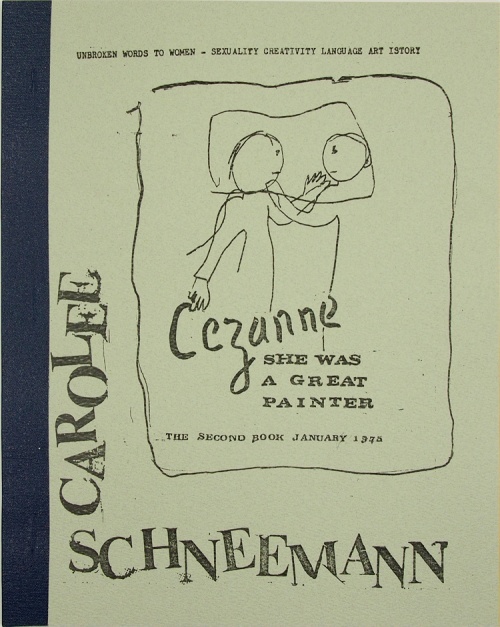

With the sexual revolution, second wave feminism and postmodern art, representations of nude bodies and genitalia, in general, have become more prominent. Very daring works, such as Interior Scroll by Carolee Schneemann, featured vaginas (yes, not vulva) in a challenging way, with the goal to make us reflect through shocking our expectations, assumptions and hegemonic ideas. In this performance, showcased for the first time in 1975 in New York, the artist reads an excerpt from her book Cezanne, She was a Great Painter. The reading is interrupted and the performer takes off the apron she was using and starts taking a scroll out of her vagina.

Many of these postmodern works have been analyzed through a feminist lens, which is fair enough and I believe necessary. Now, what if – and I’m here proposing, I know it well, a bold suggestion that might disturb people more than a woman taking a scroll out of her vagina – what if we normalize it? The idea here is that we start being okay around the representation of the human body – all of its parts.

What if portraying a female vulva was okay and it could be studied not only as a feminist work but as art? An artist wouldn’t have to be an activist for deciding to portrait a vulva. It could, instead, be considered normal to represent it as any other part of our constitutive material selves. We could focus, in such case, on not only the content, but actually think of the artistic techniques, as we do with any other work of art. Maybe, for that, we should study this part of our bodies a bit more (like actual anatomic and medical research), research about past representations and try to understand the meanings and symbolic meaning they carried, so we can reconceptualize such controversial body part in our present. Who knows, in this way, we might someday even see the representation of a clitoris in the Louvre.

Designed by: Nina Gueorguieva

Do you want to double-check the information you just received? Here are the sources the writer used.

Discovering the Humanities by Henry M. Sayre

Decoding the Sheela-na-gig by Georgia Rhoades

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/21/arts/design/the-wider-not-wilder-egon-schiele.html

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nuan/hd_nuan.htm

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/numr/hd_numr.htm

https://www.healthline.com/health/vagina-history#Even-today,-we-tend-to-be-vague-about-vaginas

https://mymodernmet.com/the-venus-of-willendorf/