Entre nous

Nightmare Alley turns at a predictable corner

Littered with weak character construction, plot holes and a predictable story arch, the only ominous alley that Nightmare Alley encounters is that of its directorial origins. It lunges into darkness and ultimately doesn’t reach the light, only seeing a dim glow at a distance.

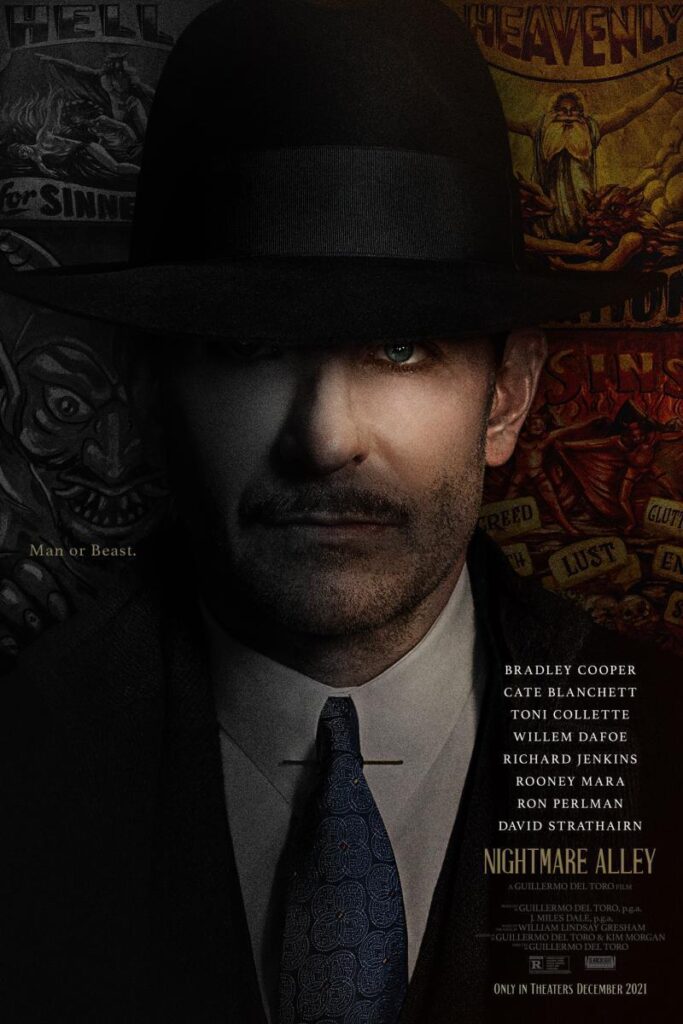

A vibrant adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel, Nightmare Alley has the wherewithal to be a fascinating evaluation of the American Dream and the dangers that befall people whom it envelops. Shrouded in a cape of mystery, protagonist Stanton Carlisle, played by Bradley Cooper, joins a carnival geek and freak show at the end of the Great Depression. Foreseeable dreams of a more prosperous lifestyle lead him to learn the tricks of the mentalist trade, where magic, seances and spirits drive a profitable business. Warned of the risks of falling too deeply into these spiritualist beliefs, he ploughs forth, planting the seeds for his downfall.

The greatest asset displayed in Nightmare Alley is without doubt found in the set and costume designs. Supple and well-researched, they offer invaluable support in evoking the time and places in which the story unfolds. Sets and backdrops dip our toes into the squalid and tarnished dignity of a local carnival show, with a colourful cast of characters and types: the clairvoyant, the little man, the strong man… Creased canvas and trodden grass make one smell the grease and popcorn. Cate Blanchett’s psychologist studio instead abounds in lacquered veneers and mirror-finished marbles, in the clinical geometric shapes of the late Art Deco. Likewise, picturesque images are formed by costumes, each for a different type: Ms Blanchett in Joan Crawford shoulders, and Willem Dafoe, as the conniving carnival owner, in a lurid fedora.

Symbolic imagery often leads one to wonder its meaning for no particular reason, such as a malformed child preserved in a pickling jar. Nevertheless, visuals draw the audience into an exploration of the pursuit of the American Dream of success, as it leads the protagonist to a lethal quest of meretricious and unattainable goals. But a problem incurs if the weight of a film is carried by set design and atmosphere alone – unless you are Stanley Kubrick and you are filming Barry Lyndon. Composer Oscar Hammerstein once said, “you don’t walk away from a musical whistling the sets;” nor does one walk away from a film pondering the motivations of a costume.

Perhaps the greatest disappointment comes with the role played by Cate Blanchett, which offers no heft or substance for the otherwise greatly talented actress. Depicting the femme fatale par excellance, Ms Blanchett’s name alone should already ensure quality brought by her extensive experience. Yet even her talent cannot overturn the weaknesses of the character construction.

The shining moment, which also explains the brilliance of the movie’s first half, comes with the introduction of David Strathairn’s character. Subtle, nuanced, and entirely convincing, Mr Strathairn’s “Pete” veers between moments of alcoholic oblivion and paternal guidance for the ill-destined protagonist. It is he who warns Bradley Cooper not to fall into the trap of the relentless social climber – and when advice is given by a man who can read the future, the results are nothing if not predictable.

And this is where the weaknesses of the film come to the forefront: expectations are built to unimaginable heights in the first two thirds of the story, with an unabating sense of sinister suspense, entirely appropriate for the noir genre. Yet once the climax is reached, with a turn to gory violence only surpassed by Quentin Tarantino, it is exactly these expectations that are let down. The heavy-handed manner in which Cooper is faced with moments of warning and opportunities for redemption, which are all rejected with the character’s assurance of success, is already more than an indicator for the audience that Cooper’s prospects are not rosy. So his inescapable demise is not so much a surprise as a fulfilled expectation, which however unravels without deriving much emotion. The twist with which the film ends doesn’t startle as much as it makes one smile in amusement at their own ability to recognise what was coming.

As an entertaining detour into a genre less commonly seen, it certainly is worthwhile. In costume and scenic values it also repays in its contract with the audience, as do a number of performances. Yet, despite its assets, which are numerous, Nightmare Alley ultimately doesn’t recuperate on the promised tensions it builds, and the emptiness that lies behind the American Dream also seems to lie behind the promises of thrills and chills of Nightmare Alley.